Testing for Dravet Syndrome

Although Dravet Syndrome is a clinical diagnosis, a confirmatory genetic test for can be helpful in many ways. It helps to prevent misdiagnosis, avoids further unnecessary investigations, and enables earlier and better-informed treatment choices, including access to new therapies and clinical trials that require confirmation of a SCN1A genetic variation.

Genetic testing is recommended no matter the age of the patient.

In terms of aiding diagnosis, it can be especially beneficial for very young infants, where it's hard to get a clear diagnosis of Dravet Syndrome from symptoms alone, and for adults, where the early signs and symptoms of Dravet Syndrome may be lost from their medical history.

What is the genetic test?

The genetic test typically involves taking a blood sample from the individual with suspected Dravet Syndrome. It could also be a DNA test from a cheek (buccal) swab or a saliva sample. The sample is sent to an accredited laboratory, where it is screened for evidence of a change in the genetic code, particularly in the SCN1A gene.

The type of test may vary depending on where you are in the UK. It might be an epilepsy gene panel or whole genome testing. Single gene testing is now rare and the accuracy of genetic testing has improved considerably in recent years. If a patient tested negative for Dravet Syndrome more than 5 years ago, but you still suspect they have the condition, it may be worth requesting a re-test.

Why does Dravet Syndrome occur?

Dravet Syndrome is caused by a change in the genetic code of one of the brain's proteins, which subsequently alters the way in which the brain functions. In around 90% of cases, the genetic change that causes Dravet Syndrome is 'de novo', meaning the condition is not inherited from parents.

More than 85% of people with Dravet Syndrome have a change (or mutation) in a gene known as SCN1A (short for sodium channel alpha 1 subunit). The SCN1A gene contains instructions (genetic code) for the creation of an important type of protein in the brain, known as a sodium ion channel. A mutation (variation) in the code of the SCN1A gene may lead to the faulty functioning of this sodium ion channel protein.

Our son had his first seizure when he was three months old, a lengthy tonic-clonic seizure lasting approximately 40 minutes, which required an emergency night-time visit to hospital. This became the pattern for years – frequent prolonged seizures, stays in hospital, referrals to larger hospitals with epilepsy specialists, tests and more tests and cocktails of various epilepsy medications. He was diagnosed as a child with generalised epilepsy. It wasn’t until he was 36 years old that we finally had a genetic test and a Dravet Syndrome diagnosis. This came as a great relief and with better, more targeted drugs as a result, he is having less seizures and his ability to learn has increased.

What if the genetic test is negative?

If someone doesn’t have a positive or confirmatory test for Dravet Syndrome, the condition still shouldn’t be ruled out if its observable clinical characteristics are typical. It just means that no mutation was found. It is important that negative test results do not prevent a clinical diagnosis of Dravet Syndrome, nor prevent families from accessing support that they need.

Around 10 to 15% of people with Dravet Syndrome either have no detected SCN1A mutation, or have mutation(s) in genes other than SCN1A. This includes: CN2A, SCN8A, SCN1B, PCDH19, GABRA1, GABRG2, STXBP1, HCN1, CHD2 and KCNA2.

What if the genetic test is positive for SCN1A?

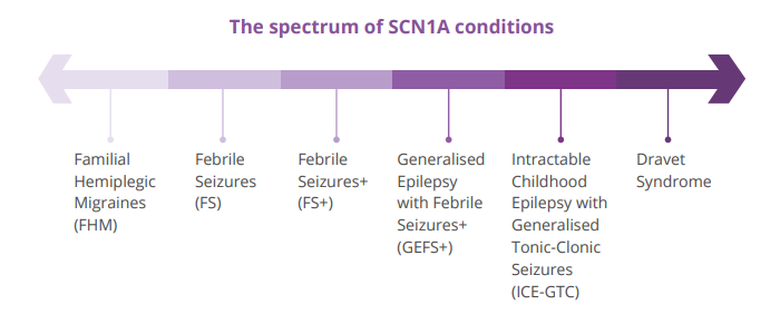

A confirmed SCN1A mutation doesn't necessarily mean that the patient has Dravet Syndrome. There is a spectrum of SCN1A conditions and Dravet Syndrome lies at the severe end of that spectrum. Other SCN1A mutations are associated with less severe forms of epilepsy, such as Genetic Epilepsy with Febrile Seizures + (GEFS+). However, clinicians can still be confident about making a diagnosis by looking at the genetic test results alongside the patient's clinical history.

The SCN1A-Epilepsy prediction model - confirming Dravet Syndrome vs GEFS+

Even with a positive genetic test and the clinical presentation of the typical characteristics of Dravet Syndrome, clinicians can still be reluctant to make a diagnosis until developmental delays are observable (around the ages of 2-3), in case the patient has a milder form of the condition, such as GEFS+. This period of 'not knowing' is extremely challenging for caregivers and, critically, it can prevent infants from accessing appropriate treatment at an early stage, which can make a positive difference to long-term outcomes.

Today, advances in the analysis of genetic testing means that clinicians no longer need to wait for symptoms to evolve before confirming Dravet Syndrome or GEFS+.

In 2021, an international collaboration of researchers led by Professor Andreas Brunklaus et al, developed the SCN1A-Epilepsy Prediction Model. This model calculates the probability of developing Dravet Syndrome versus GEFS+ based on a given SCN1A variant and the age of seizure onset. The model considers the potential effect of the queried variant and compares it with an international database of 1,018 SCN1A patients with Dravet Syndrome or GEFS+ from seven countries. The model is intended to be used only by healthcare professionals. You'll need to input key information such as when the first seizure happened. The result allows you to predict if the person will be likely to develop Dravet Syndrome or GEFS+.

Genetic counselling

If you’re referring someone for genetic testing, it’s a good idea to refer to their family for genetic counselling too. A 2021 Dravet Syndrome UK survey found that while nearly all (95%) respondents had a genetic test for the person they cared for, unfortunately less than half (43%) were offered genetic counselling.

Genetic counselling provides support with the emotional and family implications of a genetic condition. It could be supported with coping and adjusting to a diagnosis, or help with how to tell other members of the family about the possibility of the condition being passed on.

A neurologist or paediatrician will need to refer the family to their local NHS Regional Genetics Centre or to a private provider. More information about genetic counselling is available via the NHS website, including a list of NHS genetic centres.

“Certain types of gene tests, with the clinical picture, allow doctors to be quite confident of a Dravet Syndrome diagnosis. Genetic testing allows us to think about what the right treatments might be for someone, at an early stage.”

Professor Sameer Zuberi, Consultant Paediatric Neurologist

Video: The importance of early genetic testing and diagnosis

Click here to hear more from Professor Sameer Zuberi in this short clip filmed at our 2021 Professional Conference.

Diagnosing and treating Dravet Syndrome

Discover the typical features of Dravet Syndrome – intervene early and you can change someone’s life.

Guidelines, key publications and other resources

Quick links and other educational resources.